For the Hot Docs 2024 festival, I focused on documentaries centered around resistance and resilience. Now, more than ever, apathy and detachment has become a mode of being. We’re presented with an image of a degrading future: genocides in Palestine, Syria, Darfur, Sudan, and many more, too many more; extractivism and the catastrophes of climate change; erosions to public services like healthcare and education; a closing in of social circles, a strange aloofness in the world.

The films presented herein challenge those notions and ask us to suspend our hesitations. After all, indifference is a predisposition for the privileged, but an impossibility for many.

Daughter of Genghis – Dir. Kristoffer Juel Poulsen, Christian Als (Denmark, Sweden, France)

Set in both Ulaanbaatar and the Mongolian steppes, we follow Gerel; a fierce woman grappling with the death of her husband and providing for her young son, Temuulen. Shockingly, she also spearheads an ultra-nationalist party reclaiming the swastika as a mongolian symbol of strength. Her most vocal concern is Chinese involvement in Mongolia. Gerel wants to push them out, starting by raiding massage houses to shame women for their sexual exploitation by foreigners. However, when she needs money for her family, she makes the hard decision to leave her son in the city and take on a job at a Chinese construction site in the Gobi desert.

Throughout seven years, this film shows a candid and intimate glimpse into Gerel’s life, exposing profound vulnerability as she comes to terms with loss, identity, and motherhood. Her resilience and transformation argues a way forward, through grief and uncertainty.

Death of a Saint – Dir. Patricia Bbaale Bandak (Denmark)

This film is a deeply personal journey of director Patricia Bbaale Bandak. Patricia travels to her birthplace of Uganda to find out why her mother was killed when she was a toddler. While this film can appear as true crime at first glance, the murder is only one moment interwoven into the story of her mother as a person. Rather, the director uses memory to explore motherhood and loss, finding new connections with her mother, and directly speaking to her through the camera.

Patricia’s family members also play a key role: her father is reluctant to discuss what happened on the night of his wife’s death but breaks down and walks away at the memorial gathering; her brothers bookend the film with their love, understanding, and humor; and her daughter, Imelda who was born 24 years on the day her mother was killed, and shares her name, asks for her own mother to come back to Denmark. Combining the intimacy of family with images of birds and flowers, we can trace the edges of a stranger through the lives she impacted.

The Broken Goddess – Dir. Ximena Pereira (Chile, Venezuela)

A statue is more than what it symbolizes. In Caracas, the statue of Maria Lionza occupies an unusual space in Venezuelan society. Revered as a goddess of love and nature through the blending of many cultural beliefs, she’s a beloved cult figure and the anchor point of this documentary. From her tenuous location between literal highways, she guides her followers and orients the viewer towards a larger narrative of time and belonging.

Ximena Pereira’s personal experience in the diaspora blends with the tenuous presence of the statue as it’s replicated, broken, and reimagined. The result is a beautiful doubling of images and overlapping dialogue, which give both stories slightly different trajectories yet interconnect seamlessly.

We Did Not Consent – Dir. Dorothy Allen-Pickard (United Kingdom)

Three anonymized women wearing masks confront the violence perpetrated on them while part of animal rights groups. They watch two actors–a woman coerced into a relationship by an undercover cop pretending to be their lover and ally– portray intimate scenes from their experiences. As the pair act, the women pause the moment to give feedback into what they went through, and what the police officers were thinking. This breaking of the fourth wall with bitter reality informs the viewer and audience alike. At the same time, it changes the overall presentation, allowing the women to reclaim their agency from these memories.

This film captures the cruelty of police and leaves the audience with a sense of dread. The conclusion reminds us that these events were not isolated to one group of people, nor did they happen long ago. Anyone could have been a victim of such manipulation and deceit. And, what justice can be found when the perpetrator is the law?

Smiling Georgia – Luka Beradze (Georgia, Germany)

In Georgia, a hopeful politician tours the countryside, camera entourage at hand. He hugs women for the camera and tells them, “We will solve each and every person’s dental problems because I’d like Ms. Eteri and others to smile a lot more… so that they are always in a good mood, and smiling.” This promise he (on behalf of The Georgian Dream party) makes is not just one of words. In the impoverished countryside, townspeople line up at a mobile office with the hope of getting a brand new smile, just like a ‘Hollywood celebrity’.

But, in the midst of dental procedures, The Georgian Dream loses the election, crushing these aspirations. The irony isn’t lost upon those left in the lurch. Left with open mouths and missing teeth, we meet the people who, years later, still have nothing and have little means to alleviate their situation. So, they continue to wait.

Beautifully slow and languid, Beradze captures the passive resignation of the town’s ageing population. As they are confronted with new promises by politicians and journalists alike, they discern for themselves a path forward.

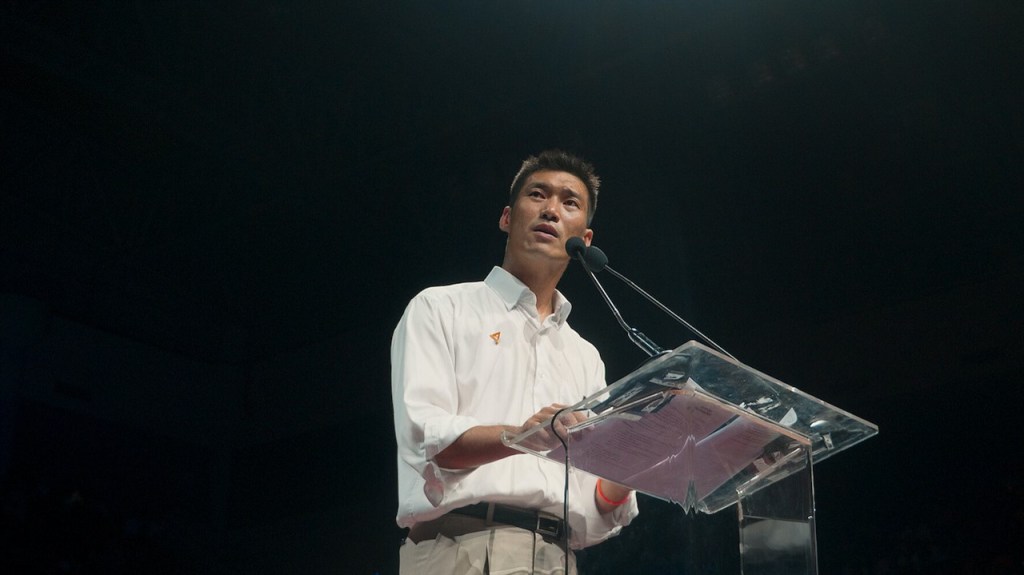

Breaking the Cycle – Dir. Aekaphong Saransate, Thanakrit Duangmaneeporn (Thailand)

Perhaps one of the most hopeful documentaries on this list, Aekaphong Saransate and Thanakrit Duangmaneeporn follow the rise of a new political party in Thailand called the Future Forward Party. “A coup every six years.” Explains Thanathorn, party leader and inadvertent emblem of the movement, “In 86 years, we’ve had 20 constitutions. A new constitution every four years.” This pattern of political instability is the cycle that must be broken.

Over a year, the party rises in power, inspiring everyday people to take part in politics. At the same time, we see staunch resistance from the government itself; the opposition party, senators, and even the election committee all pose a challenge to the viability of the party’s success. The party and its members (including those from the LGBTQ+ and indigenous communities) continue to persevere through their earnest belief in democracy as a counter to coups. The ending is bittersweet, yet continues to open the door to new political possibilities and imaginings.

Porcelain War – Dir. Brendan Bellomo, Slava Leontyev (Ukraine, United States, Australia)

In Porcelain War, three artists find ways to bridge the gap between art and war, exposing the fragility of life with the determination to resist. Slava, Anya, and Andrey utilize their skills to bring hope to their homeland. The title, based on Slava and Anya’s work creating intricate porcelain animals, refers to the delicateness of the material. While easily broken, it endures.

Contrasting battlefields, forests, and Kharkiv, the three artists navigate their own relationship to the war. Slava trains ‘former civilians’ for combat and is part of a special operation that uses drones. Anya stays in the city to continue making art, including painting a drone in red and white like a dragonfly, which is then used to drop bombs on Russian targets. Andrey, unable to paint, turns to film as a way to capture the realities of war. This lens portrays the immense contrast between art as a joyous, beautifying medium with the devastation at their doorstep. In one scene, soldiers in a special unit hold a porcelain dragon, tenderly talking about its pastel spots and small spikes. A little later on, we see many of the same soldiers now in combat, filmed with cameras attached to themselves and drones overhead.

The Everlasting Pea – Dir. Su Rynard (Canada)

While a scientist performs experiments on her subject, a pea plant, her subject dreams of its history, re-envisioning its past within the Roman coliseum. After the Romans abandoned this landmark, it sat vacant, allowing for a unique ecosystem including the pea to grow unfettered. During this time, British botanist Richard Deakin catalogued this flora. He deduced that many of them were not native to Italy. One theory is that throughout the time of the Roman Empire, many animals were imported for sport. Along with these creatures came seeds, whether stuck to their fur or inside their bellies. After laying dormant for so long, they were able to flourish once more. However, much of what Deakin had reported was long extinct at the turn of the 20th century, and those currently remaining are dwindling in number.

Within each plant is not only a genetic history, linking back to its primordial roots, but an affectual history that surmises a larger, relational past. The pea plant lives on, through the experiences of the Roman Coliseum and outwards, resisting its extinction.