There is a rare moment of consciousness while watching a film when you realize what you are watching is forthrightly unique. This is the case for Argentinean director, Melisa Liebenthal, latest film: El Rostro de La Medusa (2022). Aptly showcased in the 2023 edition of the Festival de Nouveau Cinema, Liebenthal’s film is a mixed-media tragicomedy that merges animation, documentary and literature. Starting from a simple question, El Rostro de La Medusa, follows Marina (Rocío Stellato) as she wakes up one morning and her face is no longer what it used to be. She then has to confront the construction of the self and how much of it changes once her physical appearance is not the same. The film navigates through relevant questions and issues around personal identity, social relationships, and our connection to the world around us.

Juan: How was the film brought to life?

Melisa: This fiction arises from a documentary process because I started the project with some questions about our relationship and fascination with animals. With these broad questions, I began my research by going to different zoos and aquariums to capture images of what I found. What quickly caught my attention was that, for me, people had an almost desperate desire to connect with animals, to be seen, to find and lock eyes. From there arises the notion of the face. The question of what a face is, why is it essential for our identity, and how we connect? What happens with animals that do not have a face, like the jellyfish (hence the title of the film “The Jellyfish’s Face”)? I believe they have an identity. However, I do question myself, is it possible for us to relate to an animal that doesn’t have a face? These abstract questions started very distanced from each other; I wanted to make a movie, not an academic thesis. I also didn’t want to make a cold and cerebral documentary, and that’s where the idea of fiction comes in, the idea of having a character who embodies these questions.

J: The project started as a documentary, then turned into fiction, so when did animation come into play?

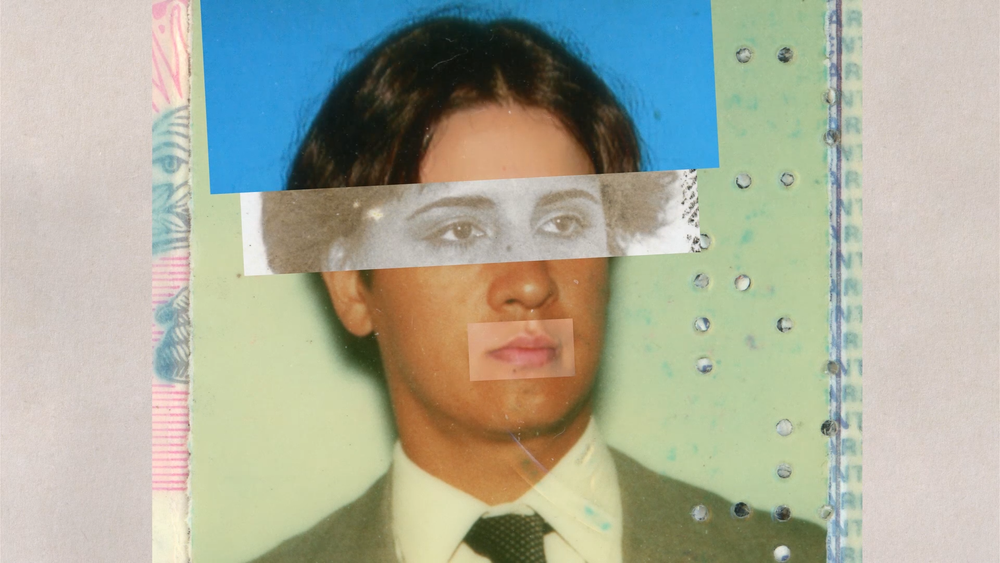

M: Animation comes into play in the scriptwriting process. Our script was already a collage in itself, filled with scraps from my notes from my visits to zoos. Animation then took on a more significant role in the editing. In fact, I had written a fairly brief voiceover to punctuate certain elements, giving the viewer reading queues. When we tried that and it didn’t work for me. Verbalizing things killed some of the poetic potential and closed off the meaning of the film. That’s when I started trying the idea of the blue linework, which comes from some drawings I found from my childhood. Children usually draw faces like potatoes with lines, two dots, and a line—the minimal expression of a face. Taking that, I started playing with the idea of marking archival photos with the blue linework to guide the gaze to what was important to me. That’s how the idea grew, and the voiceover disappeared. What remained was the animation, which is much more playful and vibrant, and also connects very well with the idea of facial recognition, taking the language of technology, nodes, polygons, and masks. This opens the door to discussing how the face defines our identity.

J: We can see that Marina’s journey of self-discovery is also through her body, not just her face. For you, how much of our identity is part of our body?

M: Not everything is in the face, although the film focuses on it as an emblem of identity. Still, I think it’s the most defining part of the body. All our senses and expressions are concentrated in the face. But it doesn’t end there; the film plays with that idea all the time. Not everything revolves around the face; there are many other parts through which we identify and connect. The film connects the idea of the face, identity, and image, but at the same time, it’s telling the character to step out of these three facets. Who we are doesn’t start and end with this visible face.

J: How do we recognize ourselves, and how do others recognize us? How much of my identity has to do with me, and how much has to do with how others perceive me?

M: I believe it is built in this exchange. For Marina, there is a great possibility of freedom by being nobody, by not being who she was, by not seeing herself as she used to. By becoming unrecognizable, a person without identification, Marina opens up the possibility of doing whatever she wants. For me, this was the most interesting concept, finding this internal liberation by dis-identifying oneself from what one believes one is and what others approve. It’s a moment when we can stop looking at those external images and perhaps look at the desire for what we want. For me, that’s where freedom lies.

J: Throughout the film, there are many moments of comedy, although it’s not a funny movie. When and why did you decide to inject these situational comedy moments into the film?

M: Humor was always in the project. We didn’t want to make a solemn or heavy film. The heart of the film is in abstract themes, which can be very intellectual, but we didn’t want it to become a dense or tedious film. From the script, Agustin Godoy’s humour was always present. We wanted to give that lightness to the film and about the pressing issues from this type of place, laughing at everything.

J: Of all the references you had, do you feel that the film comes from a literary reference, for example, the Rilke quote that opens the film, or from a more visual place?

M: The film exists more thanks to visual references, especially the images from my own research. The Rilke quote was something that came up at the beginning. I don’t remember how I found the poem, but it was something that directly spoke to what I wanted to say. The gaze and the animal’s experience, are freer and more connected to the environment than humans, who are limited by language. I included it as an element that suggests that the film deals with the perception and mystery of the animal experience, a radical otherness that is impossible to access. At first, I had the quote very much in mind, but during filming, I lost it. It was during one of the last days of editing that we decided to include it. I feel that since the film doesn’t have the voiceover tool that guides the audience, it was good to resort to this quote and other text plates that take up dialogue lines.

J: How do you understand the human need to anthropomorphize animals? How do you see this relationship?

M: My first theory was that the jellyfish was a very different, very strange animal, without a face; therefore, it has no identity, and it is very difficult to connect with them. Hence the idea of the face; I feel that this is what generates identity. Then I turned this idea around in my head. There is a sequence in the movie of animals with photos and their given names, including some jellyfish. I wanted to show there that it is perfectly possible to give an animal a personality, give it a name, and give it a fictionalized story without a face. And this is not very different from what we do with a cat, a dog, or even another person. Identity ends up being a construction, and we need it to connect with others. For me, the idea of identity is still very important, but through the film, I wanted to play with that notion, showing that it’s not so important to cling to this idea. This also comes at a historical moment where identity politics are on the rise, and we all have to check boxes of what we are (especially in North America). It’s okay to be aware of all the possibilities of a person’s being, but don’t get stuck in that… I always wonder, without finding an answer, how much of our identity defines our experience in the world, and I believe that in the end, it’s okay to break free from those limits that identity imposes. The film wants to lighten the weight of those ideas and give importance to what you feel and how you experience the world.

J: Why did you decide to finish the film the way you finished it?

M: The solution to Marina’s problem is as absurd and arbitrary as the problem itself. Without explanation, her face changes, and unexplained, everything comes to an end. There is nothing else to say when all is said and done. The film tells us (and its character) that: In the end, nothing is that important. The abrupt resolution of the film was like saying: okay, it’s over, finish, let’s turn the page.