It is always good to return to where we have always been welcomed. This year’s Festival du Nouveau Cinema brought to Montreal a sturdy selection of films that are committed to expanding the possibilities of visual storytelling and cinematic language. The selection below is a short but all-encompassing list of films that moved us, surprised us, or simply put, got us at the edge of our seats.

Anatomy of a Fall – Dir. Justine Triet (France)

Winner of this year’s Palme d’Or at the 76th Cannes Film Festival, Anatomy of a Fall is a taut, sensational masterpiece, one that subverts its audience’s expectations at every turn. After her husband’s body is discovered sprawled out in the snow—seemingly having fallen from the family chalet’s attic window—Sandra (Sandra Hüller) is accused of his murder. The truth—did he jump to his death, or was he pushed—hinges heavily on the testimony of their blind son Daniel (Milo Machado-Graner), whose witness account of the events leading up to the discovery of his father’s body finds itself as one of the key pieces of testimony at the heart of Sandra’s court trial.

Justine Triet’s latest feature unpacks the dimensions of truth that circle the case, placing Sandra and her husband’s turbulent marriage under a microscope, the prosecution seeking and inventing holes in Sandra’s narrative in equal measure. Triet’s film is a deeply layered examination of that dichotomy, probing at the nature of narrative construction and confronting the impossibilities of fact and fiction, the mutability of the truth informing a fixation with righteous judgement. Hüller’s performance transcends the screen, a commanding force and presence that is easily one of the year’s best, a ferocious kind of restraint that’s always on the edge of boiling over. It’s truly an accomplished piece of acting inside of a staggering cinematic feat, a marvellous tight-wire act of filmmaking and storytelling that accumulates into a thought-provoking triumph.

Evil Does Not Exist – Dir. Ryûsuke Hamaguchi (Japan)

A barren winter treeline bookends Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s latest feature, a provocative piece of filmmaking that balances a bitingly satirical lens with a disarming slow-burn narrative featuring numerous sequences of characters in the midst of routine: Takumi (Hitoshi Omika) collecting spring water, his young daughter Hana (Ryo Nishikawa) walking home through a snow covered forest, bureaucratic Google Meets, suited-up corporate presentations (“glamour + camping = glamping”). A disrupting temporality invokes tension throughout, the urban encroaching on the rural, the trickle-down consequences of capitalism, and gunshots echoing in the distance.

As these routines become threatened by external forces, the film cleverly reshapes itself into a knotted and thematically complex piece of art. Eiko Ishibashi’s haunting score reflects the film’s subtle melancholy, and the arresting rural landscapes—isolated, pristinely untouched—are highlights to be discovered, as are the performances across the board. It’s a film that will leave a lasting impression long after its final image fades away.

May December – Dir. Todd Haynes (United States)

Todd Haynes finds himself comfortably in his element in his latest film, a high-camp, melodramatic feature with intelligent and emotionally layered performances by stars Natalie Portman, and Julianne Moore, and the genuinely revelatory Charles Melton of Riverdale fame. The film follows an actress (Portman) researching a married couple (Moore, and the genuinely revelatory Charles Melton of Riverdale fame) whose scandalous relationship led to tabloid fodder decades prior. The actress’ arrival in the close-knit community where the couple lives unearths shocking secrets, hidden truths, and straddles the morally dubious line between representation and exploitation. It is a line that mirrors our own culture’s obsessive lust for scandal, a sensorial kind of pleasure in the consumption of another’s taboo transgression.

Doubling returns as a repeated symbol throughout Haynes’ film, with numerous shots of its characters in mirrors evoking a kind of drama of the self—and the way it’s perceived, and performed, in public and private spaces. Haynes’ capacity to disarm its thorny and uncomfortable subject matter into one of his funniest works yet is masterful, and Portman and Moore make the most out of every frame of their scenery-chewing, dementedly pernicious tête-à-tête.

L’été dernier (Last Summer) – Dir. Catherine Breillat (France)

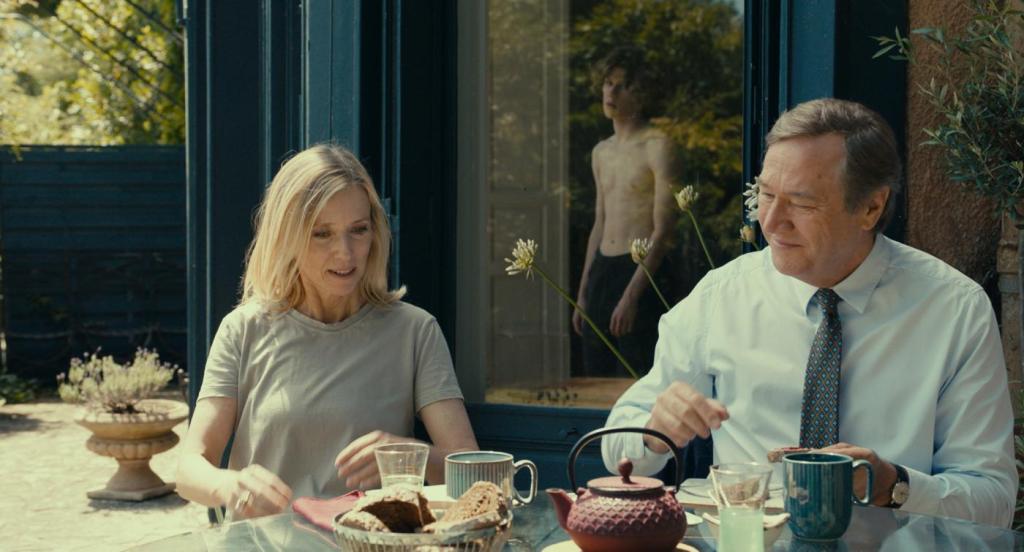

Catherine Breillat’s Last Summer is a thorny, complicated feature film that follows Anne (Léa Drucker), a lawyer who starts having an affair with her 17-year old stepson, Théo (Samuel Kircher) after he moves into her family’s home. Breillat frames the affair through Anne’s perspective, as her wanton craving draws her deeper into it with careless and reckless abandon. The film never telegraphs any moral judgement directly, instead entrusting its audience to grapple with the troubling dynamic between Anne and Théo as it slowly unravels into a more disturbing—and psychologically twisted—power play.

Both Drucker and Kircher are fantastic opposite one another, Drucker giving a commanding and jagged coldness to Anne that mixes well with Kircher’s adolescent rebelliousness, easy chemistry that adds further discomfort as Anne continues to take advantage of Théo’s youthful ignorance. As the affair comes to a head, Breillat squeezes the tension into a darkly comedic space, a psychological provocation into the social mores of human desire, and the destructive fallibility of one’s moral virtues in face of it.

Les jours heureux (Days of Happiness) – Dir. Chloé Robichaud (Canada)

Chloé Robichaud’s Les jours heureux opens with a thematic unmooring: Emma (Sophie Desmarais) adrift far from the shore after falling asleep on a floating dock. She can’t swim, but she’s quickly assisted by a good samaritan. This “in over her head” quality haunts Emma throughout Robichaud’s feature. A conductor fellow at Montreal’s Maison Symphonique, Emma struggles to balance her undeniable talents with the pressures of internal and external expectations. Her father (a commanding Sylvain Marcel) is her manager, their transactional professional relationship masking a more sinister kind of familial dysfunction, and her relationship with one of the orchestra’s cellist’s (Nour Belkhiria) acts as an emotional tether that quickly turns into a fraught lifeline as Emma’s future with the orchestra comes into question. There’s commentary, too, on the patriarchal schema of the symphony; after failing to translate her vision in rehearsal, a male colleague asks Emma: “where is your rage?” Circulating post-performance, Emma is informed by a donor that “a smile can make all the difference.”

Desmarais’ performance in both sequences—and the film at large—is revelatory, finding nuance in Emma’s struggle to stay composed in an environment that refuses vulnerability. Behind the camera, Robichaud conducts the film’s increasingly anxious movements towards an emotionally resonant crescendo that crests with a powerful force, a work that is striking for its visionary intimacy.

La bête (The Beast) – Dir. Bertrand Bonello (France, Canada)

A genre-bending film that is as staggeringly beautiful as it is beguiling, French filmmaker Bertrand Bonello’s latest film, The Beast, is a dizzying odyssey into the mind, a time and space spanning epic that asks deep questions about the nature of love and humanity. Following three loosely interconnected timeframes, The Beast’s science-fiction tinged setup is a cover for the film’s more abstract musings, a lingering feeling of existential dread that permeates the central romance between Gabrielle (Léa Seydoux) and Louis (George MacKay).

In the three different time periods in which Gabrielle and Louis’ paths cross in widely different ways, from the early 20th Century to the near-future, hints of a sinister temporal tampering—literal glitches and jarring cuts throughout—suggest an editorialization of the past, a kind of intervention into the fabric of memory that draws comparisons to Lynch and Kaufman, influences that support the unique structural puzzle that connects its timelines together.

Bonello’s film wears those influences well, his experimental romanticism defying a more conventional star-crossed lovers narrative, delicately balancing tonal shifts and capturing layered leading performances from Seydoux and MacKay. As the nature of the two’s intertwined fates slowly reveals itself over the course of the film, The Beast hints at the metaphysical tethers that bind them together—and the possibility for their manipulation through technology. It is a cerebral and high-concept watch that begs for another as soon as it ends, an intricately detailed love letter to desire, dreams, and love—in all its extremes.

Vampire humaniste cherche suicidaire consentant (Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Person) – Dir. Ariane Louis-Seize (Canada)

Evoking an energy that can be described as “quintessential Y2K teen flick”, Ariane Louis-Seize’s understated and quirky vampire creature feature nearly begs for its own merch line at Hot Topic. It’s a winking coming of age film whose effortless charm adds a layer of cool to the teen-vamp genre, playing with familiar tropes with refreshing sincerity.

Sasha’s (Sara Montpetit) plight—a vampire who refuses to feed on humans—touches at the universal dregs of teendom, and her serendipitous encounter with Paul (Félix-Antoine Benard), a depressed human teenager who sees Sasha as the perfect opportunity to help him end his life, is the kind of unconventional meet-cute that captures the magic of adolescence. A wonderful sequence between the two lip-singing along to Brenda Lee’s “Emotions” in Sasha’s bedroom is as magical as any of the most iconic scenes from the teen film canon. The film is a loving ode to its genre, full of humanity and spirit, and is bound to draw in its audience under its magnetic crowd-pleasing spell.

The Feeling That The Time for Doing Something Has Passed – Dir. Joanna Arnow (United States)

Outrageously funny, Joanna Arnow’s brilliantly titled The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed suggests a new comedic voice entering the landscape of independent American film, a sharp observer of the mundane in the everyday. A slice of life feature that plays out in observational vignettes, loosely connected by the different relationships Ann finds herself in.

Arnow’s feature recalls the explicit self-deprecating sharpness of Lena Dunham’s Girls, while leaning into a broader, drier absurdity that targets many different facets of millennial romance. From awkward post hook-up texts to the complicated power dynamics that shade in each of Ann’s relationships, there’s always a knowing register to the film that mines sincerity out of its air of detachment. It’s a film that operates on such a peculiarly specific wavelength, its odd charm and singular authorial vision stands to position Arnow as a comedic force to be reckoned with.

How to Have Sex – Dir. Molly Manning Walker (United Kingdom)

Halfway through Molly Manning Walker’s bold feature film, Tara (Mia McKenna-Bruce) stumbles back to her hotel room through the empty streets of Malia, Greece. This contemplative sequence captures the essence of the comedown of that emotional—and literal—hangover after a night of alcohol-fuelled debauchery, an ambivalence that Walker heightens to powerful effect frequently throughout the course of the feature. The film’s stark realism adds a layer of tense and unsettling weight to Tara and her friends’ rite-of-passage adolescent summer holiday. Walker’s script centres a compassionate understanding of the social dynamics that place these young women into the crosshairs of hedonistic excess—their maneuverings through which reveal a naïveté that’s worn down to a sobering reality. It’s a remarkable feature with an equally remarkable leading turn by McKenna-Bruce, a film that confronts that point of the evening where the hedonistic escapism starts to turn into something far too real.

The Zone of Interest – Dir. Jonathan Glazer (Poland, United States, United Kingdom)

It’s been a decade since Jonathan Glazer’s last feature film, the voyeuristic Under the Skin. A decade later, Glazer tackles another challenging subject—the Holocaust—with an equally voyeuristic lens in The Zone of Interest. The film follows Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel), commandant of Auschwitz, and his wife Hedwig (Sandra Hüller), as they go about their day to day lives in their home located directly next to the concentration camp. Their everyday household troubles are punctuated by the sounds of violence that unfolds beyond the walls of their garden, screams and gunshots that haunt the edges of each scene.

The film’s deliberately banal domestic rhythm is played to deeply disturbing effect, as Glazer forces the viewer to confront the horror of what it means to become lost in its meditative domesticity, the scale of the atrocities taking place on the other side of that wall as an unimaginable abstraction. It’s a provocative angle to approach its biographical subject matter, one that tackles its own morally ambiguous complicity in rendering the Holocaust as a theatrical exhibition, a new shape of grief that’s slowly uncovered across its runtime. It’s a harrowing watch, but one that feels essential in what it reveals about the nature of the mundane evil on display.