Satoshi Kon’s animated film Paprika (2006) explores the phantasmagoric and fantastic between the blurred states of dreams and reality where the hyperreal, the uncanny, and the inexplicable manifest that link the conscious and subconscious mind. Hopping through dreams, memory, and media, Paprika intertextually and self-reflexively ties these relationships together with technology as the force behind its creation and mediation. Dream logic is visually translated onscreen, opening up the endless possibilities of the technological vacuum that interfaces our everyday interactions, Paprika explores the simulacrum of being living in our present reality.

It’s a strange feeling to be possessed and affected by and register the feeling of something so immaterial. Some of the earliest memories I have are of movies and recurring dreams from when I was young, that even to this day recur under certain conditions, where my subconscious has dredged up what has now become a nightmare so vivid their effects are felt long after registered within the body’s memory with the mind rearranging its’ present transitioning to a waking state.

“I—it’s the greatest showtime!” Konakawa, a police detective who has come for help with a diagnosis of anxiety neurosis from a murder case he’s been stuck on and affecting his sleep, wakes up with a start to a young, cropped bob red-headed woman named Paprika. After what is recognized as a dream sequence captured by the psychotherapy machine called the DC mini, Paprika and Konokawa begin a dream analysis. Paprika breezily speculates and deconstructs Konokawa’s dream, similar to a film analysis starting with genre, style, characterization, and motivation. Scheduled for another session, just as soon as the girl of our dreams has arrived, she’s off and gone again to another dream.

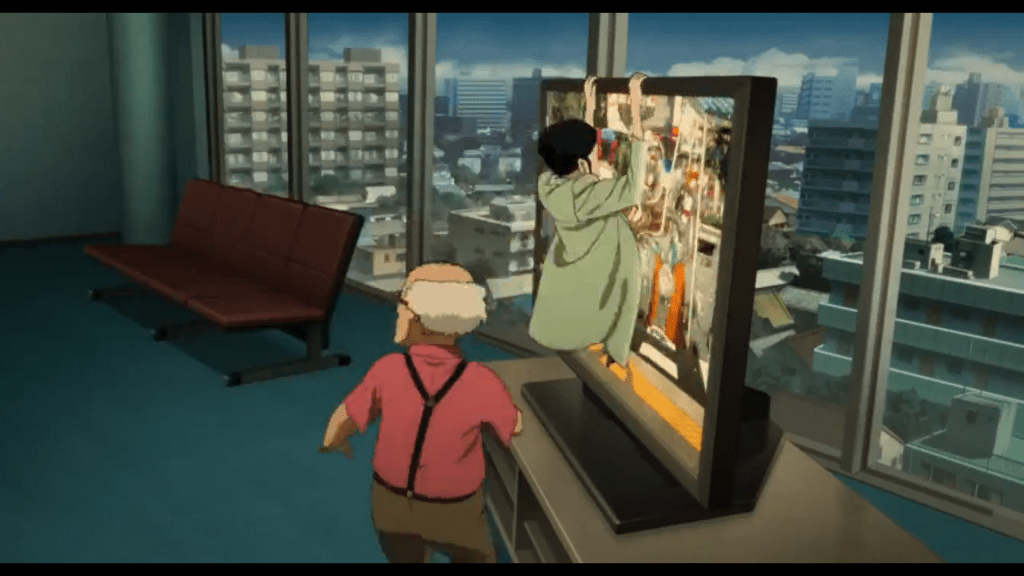

A series of lapses in time and animated transformations fill in the gap between the visual image and narrative exposition. The film embraces the overstimulation of the image and sound as an accompaniment to its attack on the senses and stretches the limits of animating narrative and editing frameworks. Recalling cinema’s early days, returning to the frame-by-frame movements of the Zoetrope to the now multimedia and multi-platform landscape from paintings, films, videos, photographs, advertising, on computers and the Internet. Fully immersed in the shifting representations of the moving image, Paprika playfully interacts with and has the ability to synchronize with and interrupt the flow of a given moment or environment in this multimedial form.

In this same manner, Paprika catches up to and merges with the form of Dr. Chiba Atsuko, a psychiatrist and researcher, she’s confronted with the theft of a psychotherapy machine called the DC mini. Atsuko quickly moves to action after Dr. Kosaku Tokita and Chief Toratarō Shima are called upon to assist in de-escalating the matter with company Chairman Inui. Knowing the potential risk and misuse of the machine without having access controls programmed into the apparatus, the Chairman rebukes the technological abomination that invades the mind. Referring to the rumours of a dream girl named Paprika as a terrorist and the number one suspect of stealing the DC mini, Atsuko defends the purpose of the device to help those in need. Shima agrees with Atsuko, and similar to the opening of the film, by the time we figure out what’s happening, meaning has devolved, and the symbolic order that upholds our reality begins to unravel at the seams. And no sooner than we’ve begun to catch up, the Chief has leapt out of a window laughing a few stories high–while shortly after, in the midst of a parade of recognizable symbols and icons of various imagined and real objects, march us into the grand illusion of the spectacle with the Chief as its appointed head. The soundtrack of the dream parade sweeps over the senses in a wonderful explosive melodic cacophony of noise that simulates the madness and mania of its’ unstoppable movement as a force that exceeds the limits of reality.

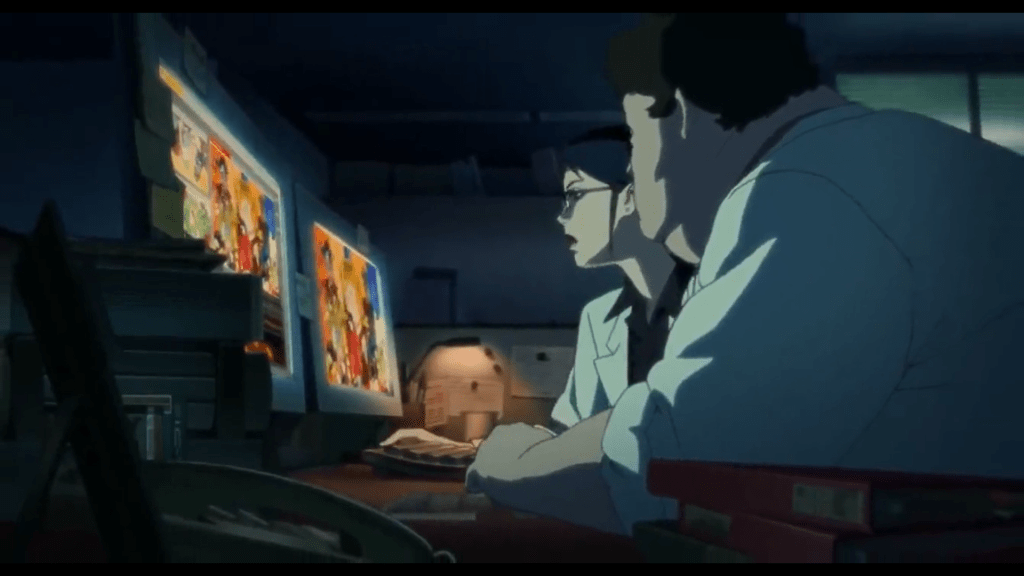

Zooming out of a computer screen with the Chief hooked up to medical and imaging machines in another room, Dr. Chiba, Dr. Tokita and Dr. Morio Osanai analyze the delusion causing the deterioration of the body and mind. Atsuko and Tokita determine that the terrorist misusing the device must also be watching the nightmare. Buying time before the Chief sinks further into the delusion and on the hunt for a missing researcher named Himuro, who they see appear in the parade, they connect him to the DC mini’s disappearance. In pursuit, Osanai alludes to Atsuko and Tokita that, “a genius produces a lot more than he realizes. Himuro was jealous of Dr. Tokita. Even I feel bitter towards you sometimes, Dr. Chiba. No matter how hard I try, I’m not as good as you. I feel powerless.”

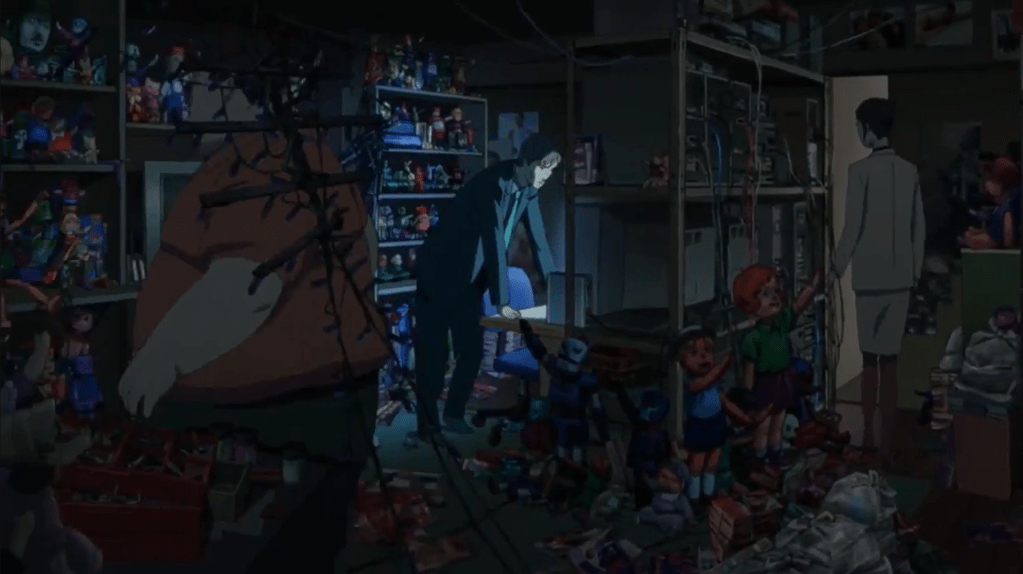

Dr.’s Chiba, Tokita, and Osanai break into Himuro’s apartment, who as an otaku, has excessively filled his environment to the brim with his obsessions and fixations. As a representation of this repressed otakus’ mind, the apartment establishes the connection between one’s mind and the environment that one surrounds oneself in and around that may or may not be reflected in or connected to one’s upbringing, shame, traumas, desires, or fears and can at times manifest to the point of self-delusion or destruction. With technology as the link that distorts the divide between reality and dream spaces, in this case, Himuro’s otaku influences leak into his work as a researcher, opens up new pathways of inquiry into the unexpected. Atsuko, following her intuition, led on by a blue butterfly and a doll that always appears just outside of her peripheral vision, leads her to a secret opening where she’s led into an alternate space. Warned by Paprika and promptly bushed off, Atsuko follows the butterfly and the doll until the illusion dissipates before her eyes, and the ground falls out beneath her, only being held on to desperately by Osanai. Recovering at a family restaurant, they narrow down the projection of the nightmare to an anaphylactic reaction that has allowed the dream’s transmission to spread through those who have used the device the most and are the most vulnerable or susceptible to being sucked into the delusion themselves.

By setting up the film as a psychological thriller, the investigative dream work used to frame the narrative using visual and audible referents, symbols, and totems appear and reappear throughout that, simulates the instantaneous reactivity and loss of control one has over the direction of their dreams though we may appear to have to illusion of control–asleep or awake. Paprika asks Konokawa in a therapy session in an online meeting space with a knowing smile, “Don’t you think the Internet and dreams are similar? They are both areas where the repressed conscious mind vents.” Konokawa, while interested in the analysis of his dreams, also diverts his attention to learning the other identity of Paprika outside the virtual and dream space, but is baited back into speaking about his past and is forced to confront the true nature and the source of his anxieties. At the same time, the dream transmission continues to spread, causing reality and the dream space to overlap more with increased cases of those being affected, suffering the same nonsensical violence and destructive consequences left behind. This paralleled with the team now being restricted from using any other psychotherapy machines as ordained by the Chairman condemning the project entirely, Atsuko recognizes an image of a character on Tokita’s shirt as they dismantle the lab’s equipment. Using her intuition and seeking out the same theme park that she first entered in Himuro’s apartment, Atsuko and Tokita recall the uncanny details of the imaginary space. Hanging in this suspense of deja vu, as they find the doll where the previous dream ended, Paprika suddenly appears to warn Atsuko just as Hirmuro’s body comes crashing through, barely sparing her from being crushed.

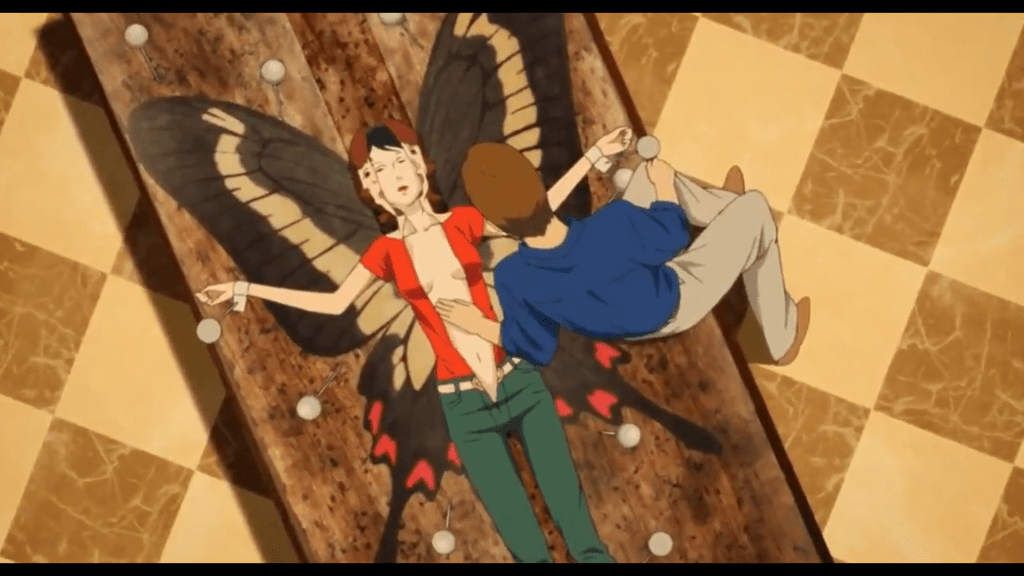

In a less violent way, Konokawa and Atsuko are drawn toward one another as they recognize each other’s energies as they meet in a physical space for the first time, through the now public investigation of the effects of the psychotherapy machine now known. Tokita explains to Konokawa, “Isn’t it wonderful? The ability to see a friend’s dream as if it were your own. To share the same dream.” Though they separate, pursuing different threads of thought with the investigation, the parade continues marching as Tokita, Konokawa, and Paprika are swept up in its delusion. With Tokita swallowed up by the nightmare parade now exponentially spreading throughout the city in his reckless attempt to rescue Himuro, Atsuko, instantaneously transforms into Paprika and dives into Tokita’s merged dream on a mission to save him. With the development of the project and the lives of everyone at stake, Paprika flits through the nightmare with the Chief monitoring her as she looks for clues. As she peers further into the unstable construction of the dream space, moving past the superficial layers, Paprika is led down the ever-shifting mayhem of the ever-evolving mystery, and she, too, becomes caught up in the delusion.

Slipping in and out of the dream space and reality through the pervasive influence of technology closely parallels the creative process when approaching the ways in which we unravel the various meanings and paradoxes of our experienced reality. In many ways, the creators’ process in making art and the history of film are linked to the fascination of projecting dreams into reality. It also reveals the other side of what makes up a dream. What sacrifices are demanded to achieve or obtain one’s wildest fantasies or desires? How many versions of our dreams or ourselves have died, haunting our present? To what end will we project our deepest insecurities, biases, and fantasies onto one another until ultimate satisfaction is reached–and if it’s not enough, then what? Using technology as the device that frames the introduction into the collective dream, the mundanity of the absurd that orders the experiences of our shared realities is tested. Ruled by an indulgence in distraction, delusion, and desire, Paprika questions the foundations for the collective dream, where memories and histories are created and controlled through the technological framework that we’ve constructed in and around ourselves in our present reality. The invasion of the dream space, in reality, is consumed by the simulacrum and subsumed by the phantasmagorical spreads—meshing together what is real and what is imagined until their separation is unrecognizable.

Media theorist Jean Baudrillard describes that when the copy becomes more “real” than the “original” it denaturalizes and unsettles the distinction of the now transmogrified hyperreal. He continues to say, “The impossibility of rediscovering an absolute level of the real is of the same order as the impossibility of staging illusion. Illusion is no longer possible, because the real is no longer possible. It is the whole political problem of parody, of hyperstimulation or offensive simulation, that is posed here.” (14) As Chief Shima and Atsuko speculate, “That’s not Himuro’s dream anymore. He’s an empty shell. He was invaded by a collective dream. With no access restrictions, the DC mini can be used to invade any psychotherapy machine. Every dream it came into contact with was eaten up into one huge delusion.”

There are many ways to interpret the film, but Paprika self-referentially traces the creator’s visions from dreams to influences to its execution in whatever form that it may take, resisting (or being consumed by) the commodification and control of the capitalist apparatus that reproduces its own logic of exploitation and extraction to sustain itself at any cost; where the spectacle of horror and the fantastic collide; unable to look away where the artifact of the image remains but the meaning has devolved. In its representation of the frenzy of pleasure, hysteria, and paranoia, Kon conjures multiple iterations of cinema that reanimates awe and fascination with the vision behind the moving image through the film’s narrative and visual form. Always chasing figures already in motion, Kon’s films reflect the just-out-of-reach remnants of the dream, idea, or vision, without knowing when or if it will appear, but in pursuit of it nonetheless.

Sources:

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Glaser, University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Kon, Satoshi, director. Paprika. Madhouse, 2006.