Many, maybe too many, artistic reflections have been made about life in the new millennium, especially in cinema. Some tend to romanticize our future; others are more worried about a pessimistic future. However, Oshii Mamoru’s Ghost in the Shell series might be one of the best studies on the state of humankind. Conformed by two animated films, Ghost in the Shell (1995) and its sequel Ghost in the Shell: Innocence (2004), Oshii’s contemplation of humanity is a layered story that navigates government corruption, over-reliance on technology, the commodification of labour, individuality and even the ethics of owning a pet. Yet, the film’s story is threaded on a bleak, bone-chilling, statement that reverbs like a loud bell tolling: we are worthless.

I for one, am not someone that needs a reminder of my life’s worth. Fifteen minutes in the world are enough to realize these unpleasant truths. But Oshii’s films feel much more than just a recollection of eclectic high-brow social commentary; Ghost in the Shell is a fleshed-out memoir of two high-tension notions and the energy they share and lose as they try to pull away from each other. The advent of the digital age gave us the sense that life is as fleeting as ever-lasting. When presented with the chance to accrue knowledge beyond knowledge, perhaps finally grasping the raison d’etre of life itself, the Major, a sentient android chooses to follow this path. Her decision, framed on a highly dramatic violent stand-off, is where Ghost in the Shell balances its credo. The Shell is fleeting, the Ghost is everlasting. Who knows if presented with the chance to leave behind our body, an empty carcass, to pursue enlightenment, I would choose as the Major did.

Can the Ghost exist without the Shell? Oshii argues information, be it algorithms or memories, can survive without an inhabiting body. But is this the only meaning for ghosts in the film? The filmmaker gives an ambiguous definition for the aforementioned term, it oscillates between phenomenological entities, human consciousness, to digital interstices, yet arguably, the most prominent usage of the term ghost is the soul. To define the human soul would be a task far too complex and possibly endless. On the other hand, as portrayed in Ghost in the Shell, Oshii’s idea of the soul seems to be a tangible concoction of memories, dreams, and motivations.

This tangible source of life sits at the mainframe of Oshii’s narrative as the primary defining factor of humanity. The Major and her friend (co-protagonist and co-android-being) Batou, are what thread this argument through the length of both films. They seem to exist in a mental liminal space that allows them to perceive and materialize what we cannot see and understand. There are two moments, two pulchrous and divine sequences in which the Major and Batou interact with the ghost–the soul–which are where Ghost in the Shell elaborates and expands its vision: the cityscape (Ghost in the Shell) and the folklore festival (Innocence).

In Ghost in the Shell, the Major takes a break from her mission to wander Newport City, an urban landscape that is an amalgamation of many contemporary cities. We travel and see the city from a subjective point of view, yet, this POV is not the Major’s as we see her sitting in a cafe, or strolling down the canal. It is uncertain what we are supposed to be looking at or searching for. There is no narration, no diegetic noise, just Kenji Kawai’s eerie soundtrack and the city. There are no faces to discern, except for the Major’s. It is not until the sequence ends and we get thrown again into the brutal violent world of the Major and Batou that we understand the cityscape’s meaning. This urban grid of cement and glass is an ode to human memory, dreams, and motivations. If we extracted the people from the city, the buildings and the streets would still speak about the existence of the greater power that erected them. Completely efface the city, and the people in it would undoubtedly rebuild a staggering monument, a space not only for physical contention but also a place where souls will be reflected. In a greater sense, the dichotomy of the Ghost and the Shell can be equally applied to the cityscape. The concrete is the carcass that conveys the human spirit.

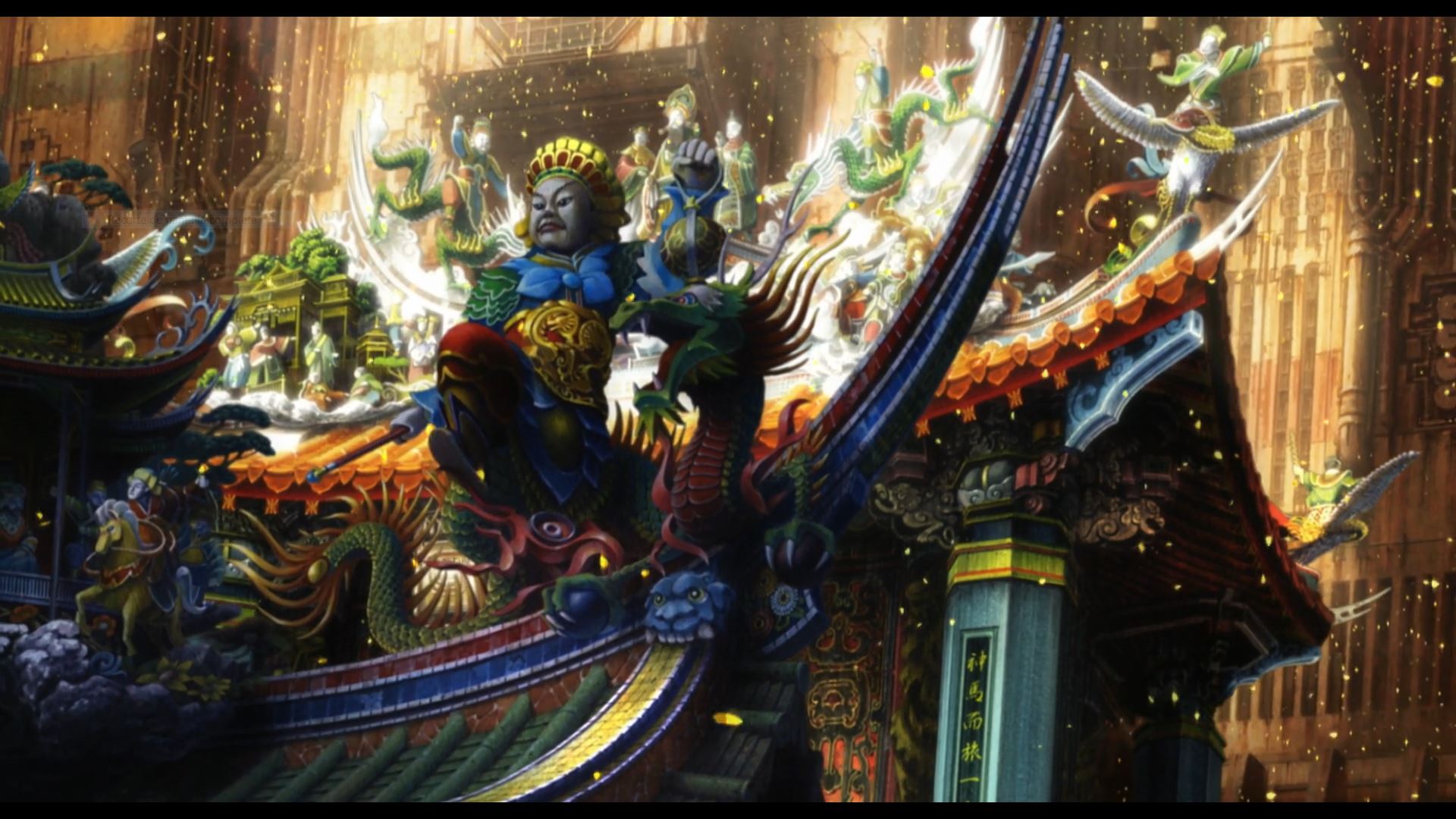

By the same token, Oshii explores this relationship in a similar fashion in its sequel: Innocence. Although focused on Batou, the concept is the same. Again, from an omnipresent first-person POV, we are transported into an intermission-like sequence where Kawai’s soundtrack accompanies images of a folkloric festival. In this case, instead of focusing on the landscape, we focus on the people, their expressions, and their movements. If the city in Ghost in the Shell was an allegory to humankind’s soul, the festival in Innocence is the direct articulation of the soul. Artistic endeavours, rituals, and the inherent sense of belonging, all are for Oshii direct reflections of the ghost. They are tangible constructions of memory and dreams. For a minute or so, we mirror Batou’s sense of peace that comes with witnessing the festival. There is nothing that stands between us and the indomitable nature of the human soul. Yet, just like it happens to the Major, Batou is thrown into the violent path he was on before this moment.

However beautiful, hypnotizing, and thought-provoking these moments are, they stand out because they are so much different in tone from the rest of the movie. They are encrusted in the middle of a grim violent story. This is where the terror sets in. The human soul, what makes us who are, is worthless; it does not change the direction the world is turning to. It is not the centre of the universe, not even the centre of our lives (although it probably should be!) The soul has become a ghost, in the most colloquial sense, an invisible entity that haunts us, but instead of opening a creaking door, or flickering a lightbulb, it haunts us with ideas of out-of-grasp idyllic what-ifs.

Working as a double-edged sword; these two moments are simultaneously a portal into what our relationship with our ghost should be and as a reminder that perhaps, even if we were in touch with it, it would not change much of our fate. This is Oshii’s mandate, a bleak chilling manifesto of contemporary souls that rather than being elaborated, is perspired by the state of the world that we live in.

Works Cited

Ruh, Brian. Stray Dog of Anime : The Films of Mamoru Oshii. Palgrave MacMillan, 2014