“Perfect purity is possible if you turn your life into a line of poetry written with a splash of blood.” — Yukio Mishima, Runaway Horses

When I first watched Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), I had never read a single work by the illustrious and notorious author Yukio Mishima. I’d admittedly, idly scrolled through his Wikipedia before when researching queer writers, but a sterile recounting of facts does little justice for the life of anyone. Especially so for the orchestral life story of the writer, famous not only for his revered status in the Japanese literary canon, but perhaps even more so for his elaborate and dramatic death by seppuku after a failed military coup. No, to truly understand the enigmatic man, you first must feel the vibrations of his life.

Biopics are one of the most difficult genres of film to successfully execute. How will this art guide the narrative legacy of another human? How do we summarize the wholeness of someone, truly? And can it make the crowd go wild? How, subjectively, can one interpret and explore the Subject? This genre is further complicated by the restrained artistic vision that is normative among biopics, with most creators resigning themselves to the straightforward, unstylized approach. This, for me, leads to a filmography of snooze fests (Yeah I’m looking at you Jobs, 2013!) Essentially creating a roughly two-hour Wikipedia article for the sake of sterile ‘realism’. This is art of idolatry–or worse–safety.

Paul Schrader’s Mishima, breaks the dry conventions of the biopic in favor of presenting a different type of ode, one that presents the truth of author Yukio Mishima’s cultivated character and psychology.

Mishima built mountains out of molehills, made the slice of life mundanity into epics worthy of canonization. To read a Mishima novel is to know him, or at least the character he expertly constructed of himself. The man is inseparable from his writing; he wrote because he lived in dreams. Every breath, every movement of his wrist was, in his mind, a Shakespearean gesture on the world stage.

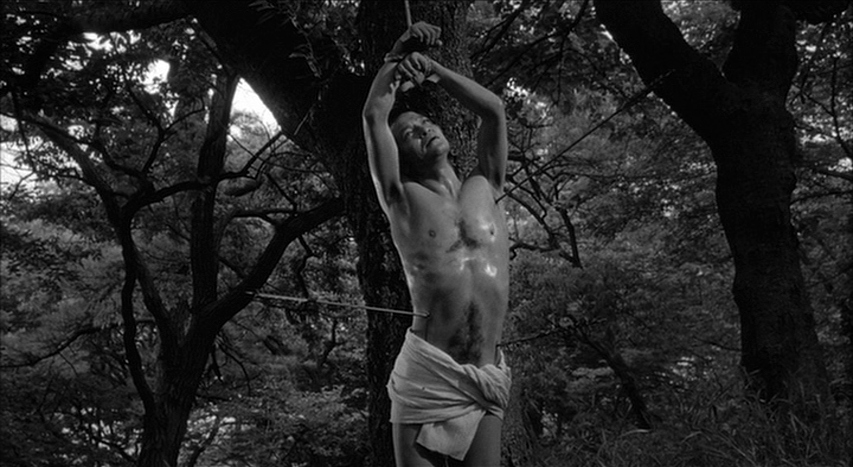

How the film successfully crafts an extraordinarily unique biopic is through the lived reality of Mishima’s life interspersed with scenes from his novels. Slingshotting us from the last day of Mishima’s life, to a theatrical rendition of a piece of his novel, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1956), to exposition of his restrained upbringing and rise to fame— all aspects are presented as equally essential fractals composing the larger portrait.

But Schrader hardly does this alone. This exquisite corpse of a film is impactful not only because of the theatrical visual aesthetics, but most notably through the bombastic soundtrack composed by Philip Glass. The soundtrack rockets us through the film, with penetrating percussion and gorgeously shredding strings Glass transforms Mishima’s fantastically human life into the epic the author was obsessed with creating.

Glass’ soundtrack elevates the experimental narrative structure and fantastical aesthetics beyond the typical biopic by pulling no punches on compositions of grandeur, shedding the subtlety of other biopics. The visuals of the film transport us to the disturbing aesthetics of Mishima, but Glass’ score pulls viewers into the grotesquely beautiful heart of Mishima’s world: a world that transfigures everyday mundanity in favor of the theater of experience

With militaristic snaps of a snare drum, you imagine a grand phalanx of Roman soldiers marching upon the Gauls, not necessarily a small unit of Mishima’s loyal followers sneaking in a military base. And the frantic movement of the strings always teeming to burst behind many of the songs casts Mishima less as the unheard, laughable lunatic calling for revolt from the rooftops, to the image of Nero fiddling atop his palace while Rome burned.

Schraeder and Glass do the ultimate justice to the man of Mishima— by carving his simple, extraordinary, lonely, beautiful life into the tableau of myth. Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters is, through the meticulous assemblage of image and music, not only a testament to a great writer, but an homage to all artists that swim through the everyday as big fish in small ponds. They sew another patch onto the quilt of self-mythologization the author dedicated his entire life, art, and death to in an utterly memorable and revelatory film unlike others of the genre. They show existence as it is: a symphony.

We as human subjects and as artists must be unafraid to tell each other’s stories. To present the true grime and luster of another’s life, to present it honestly. But that doesn’t have to mean fully literally. If all we see or seem is but a dream within a dream, then art is that dream made manifest.

As a bleeding poet and utter romantic, I obsessively escape into the fiction of reality, casting every turn of my simple life under the scrutiny of the beautiful. Even filing my own taxes could be a moment of the Sublime, or the depths of psychological anguish. If we all are to return to dust, what is to grow from the soil of where I rotted? Nothing is spared from the artist’s jaw; everything is to be chewed up, examined, and spit back out.

I will never craft my own personal militia for the sake of overthrowing the Japanese government to reinstate the emperor to the throne… certainly not. Mishima was an extraordinarily complex man: queer, secretive, proud, shameful, creative, pessimistic, and an imperialist. None of these facets of him can be dismissed.

Yet, Mishima’s story, and Schrader’s film, demand me to taste the blood of my life for every minute detail, to savor every last sickeningly beautiful crescendo until your final note fades to silence. Perhaps someone will remember, Maybe they’ll even dream.

–

Works Cited:

Schrader, Paul, et al. Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, Criterion Collection, 2019.

Mishima, Yukio. Runaway Horses. New York, Pocket Books, 1975.

Poe, Edgar Allan. “A Dream Within a Dream.” The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, 1903.