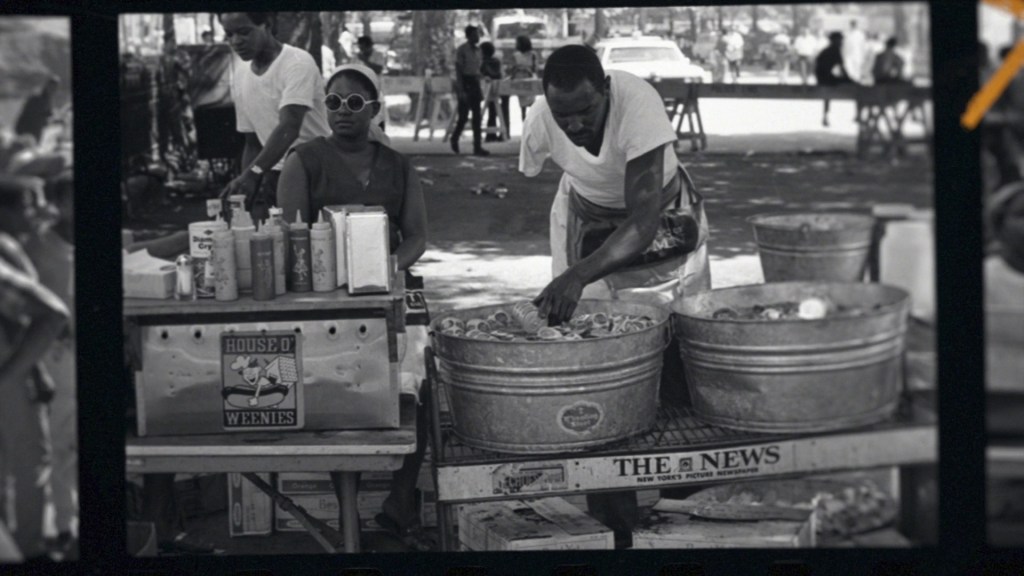

A holler. A wail. A cry out. In harmony, the crowds riled up with a surge of energy. This was just the beginning of the line-up at the Harlem Cultural Festival in 1969, right in the centre of Harlem, NY.

Ahmir ‘Questlove’ Thompson’s documentary Summer of Soul (…or When the Revolution Could Not be Televised) opens with the text on-screen:

During the same summer as Woodstock, a different music festival took place 100 miles away. Over 300,000 people attended the summer concert series known as the Harlem Cultural Festival. It was free to all. The festival was filmed. But after that summer, the footage sat in a basement for 50 years. It has never been seen.

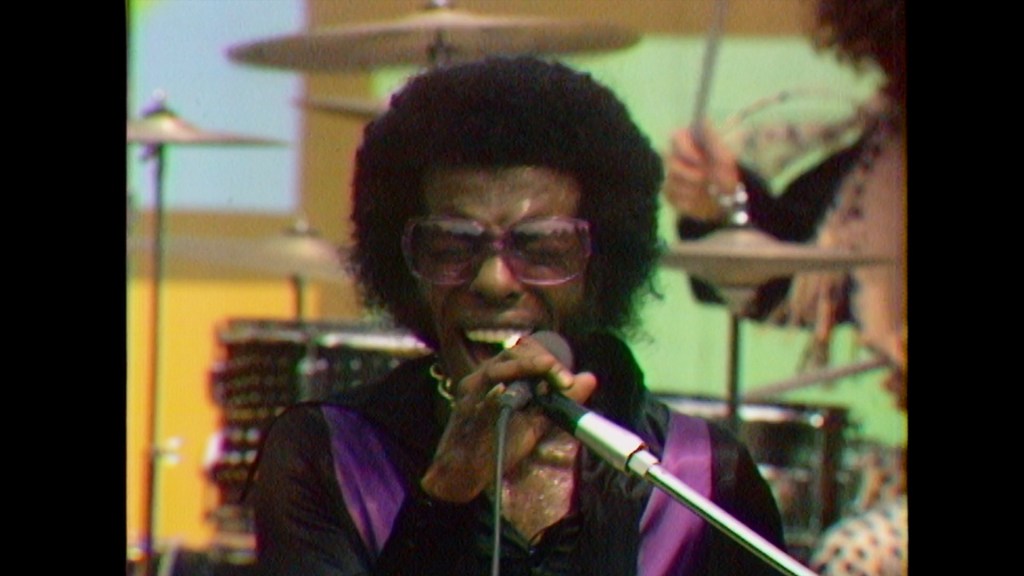

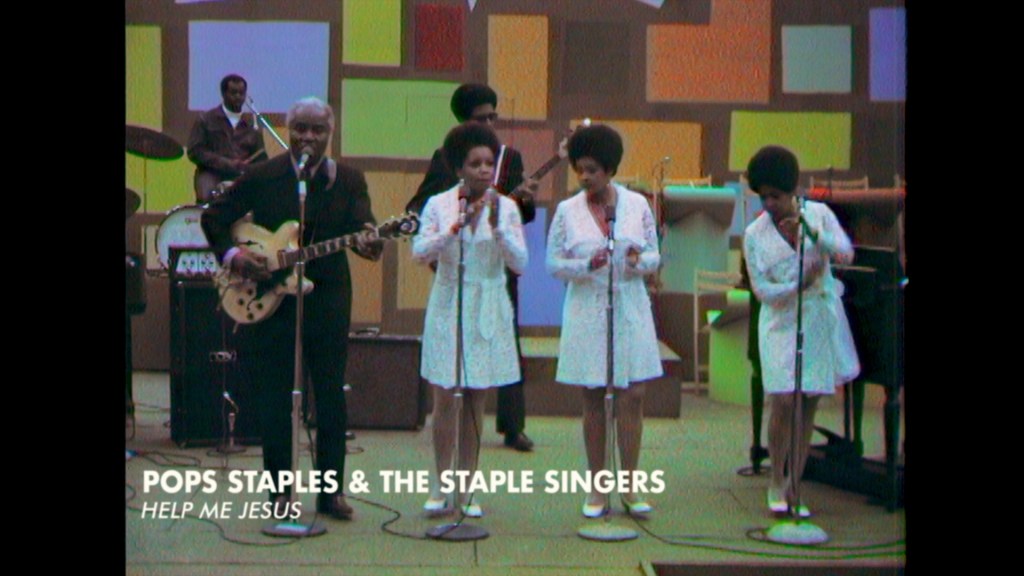

At the height of artistic, social, and cultural revolutions in 1969, Summer of Soul cycles through Black history, exploring how these sounds of protest and liberation evolved over time, bringing the Black community together amid upheaval and conflict during the Civil Rights Movement. Even though some of the most influential musicians at this time: Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, Sister Mahalia Jackson, Mavis Staples, Pops & the Staples Singers, The Chambers Brothers, B.B. King, The 5th Dimension, Gladys Knight & the Pips, and Sly and the Stone amongst many others, performed at the festival, uniting the Black community together, its existence obscured over time. Moving through jazz, blues, soul, gospel, R&B, Motown, funk, Latin, and psychedelic rock, Summer of Soul captures the largest gathering of the Black community at the Harlem Cultural Festival. Using archival footage from the recorded broadcast event, musicians, performers, speakers, and festival attendees recount the event, and other contemporary interviewees and commentators deepen the historical and cultural contexts of the period.

Summer of Soul transported me back to the music that would play throughout the spaces of my family’s house growing up around musicians of differing backgrounds and love for music, being in church, and cultural community events that celebrate our being collectively. Mavis Staples recounts the different music festivals her father and sisters would play at as part of the Staples Singers, “… Pops said, Mavis, listen to our music. You will hear every kind of music in our songs.” The older I get, the more I surrender to the sound, and even more so the kinds of songs I would sing along to but didn’t understand their meaning at the time.

The guitar was the first instrument I learned to play. I love how it croons, hums, wallows, swells, and pines…the strings bend in an infinite combination of sounds. The freedom of movement. I was attached to rock music first—I admired the carefree spirit of Van Halen, the frenetic rush and reverb of power and desire of Jimi Hendrix, Prince’s longing, heated, snarling riffs, and the rhythmic bass and twang of Bob Marley and the Wailers. Then, a clarinet was passed down from close friends we called family. Its dark wooden frame made it heavier than the other plastic clarinets; its bassy tone resonated from my fingertips through my body. Though it took time to get to know the instrument, my favourite to play was jazz, with its sliding scales and punchy progressions, dis/assembling conversations between instruments.

It’s the feeling of knowing how each note and sound hits throughout different parts of your body. Creating repetitive patterns forming muscle memory of the notes and beats—understanding the parts people play, riffing off moment to moment. Anticipating, moving towards, or diverting to other streams of sound merging and splitting off in an instant. Fluency of flow. Connecting to a deep knowledge and practice of listening and feeling the call and response from the body. If it’s fun to play over and over again, you know it’s good, and I think this is what Greg Tate, writer and musician, says when he refers to the music made by Sly and the Family Stone as “the ministry of fun.”

These experiences of feeling sound and music were everywhere around me, being in church during worship, singing and listening to traditional hymns, people lifting up their hands, speaking in tongues, waiting for their souls to stir. My father would take us from his rehearsals, and jam sessions at times. A steady beat could be heard coming deep from the basement of the house at any hour during the day before late-night gigs after his day job. The dry heat beat down, carrying the fragrance of lilac trees blooming, comfort food smells of curry and jerk spices, dumplings and plantains frying, and ginger spritzes wafted around. The bouncing reggae music from the Carifest Carnival parades in the park and the reverb of dominoes slamming on the table from impromptu family backyard get-togethers came flooding back. So did the memories of the pain, thinking alongside those songs I had tried to forget and left behind, resurfaced—familiar melodies of those who had since passed or simply moved on or away lingered on as Sister Mahalia Jackson and Mavis Staples performed Precious Lord together.

These sounds were quintessential growing up in my family. The music was the message. “How do you colour a sound?” asks Marilyn McCoo sitting beside Billy Davis, part of the vocal group called The 5th Dimension, in their performance of Don’t Cha Hear Me Calling to Ya and Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In. Summer of Soul captures sound as movement. Coming to you in, of and, from the movement, the resistance, the revolution itself. Witness to the outpour of transformative power, justice, and cool, Summer of Soul pieces together and celebrates the oral histories of Black creativity and musical expression that have been censored, culturally appropriated, and erased across history.

Sources:

Daspin, Eileen and Van Liew, Joel, editors. Motown: The Music that Changed America. Dotdash Meredith Premium Publishing. 2022.

Thompson, Ahmir ‘Questlove,’ director. Summer of Soul (…or When the Revolution Could Not be Televised). Mass Distraction Media, 2021.